The Irony of Privacy Settings: Can Lawyers Use Social Media Posts in a Court of Law?

Disclaimer: The following article is not legal advice. If you have questions or concerns regarding social media content and what could be used against you (or for you) be sure to consult with an attorney in your jurisdiction.

Just as the development of the printing press and its distribution of information had a significant, sweeping impact on the world, so too did the Internet and the storage of electronic information. The practice of law and the ability to access information relevant to a case has been noticeably impacted by the Internet age. Electronic discovery, also known as eDiscovery, of information and use of forensic experts are common in white-collar criminal activity—like when investors are involved in financial crimes. But not all the electronically stored information relevant in the legal field has to do with large-scale issues like insider trading schemes or terrorism investigations.

The rise of social media has given everyone with an internet connection the ability to receive, send, and store information in numerous formats. This article will not discuss the intricacies of forensics or the massive amounts of data stored in an investment bank's servers. Instead, we will examine how the storage and sharing of information on personal social media accounts can play out in a legal case. Most of the information below focuses on cases in New York State, which provides a good lens to view social media issues. Remember: Different courts have used a variety of approaches.

Privacy Isn't a Given

Many social media users utilize their social media privacy settings in one way or another. Some people may have private Instagram and Facebook accounts but a public Twitter account. Or they may have a private Facebook account and public Instagram. Different platforms allow users to fine tune exactly what they want other followers, users, or browsers to see.

But how much privacy do you actually have? Limiting a photograph you post to a specific audience is more private than making it public. But do you really have an expectation of privacy when you post to hundreds of "friends", even with your privacy settings activated?

What Can Be Discovered?

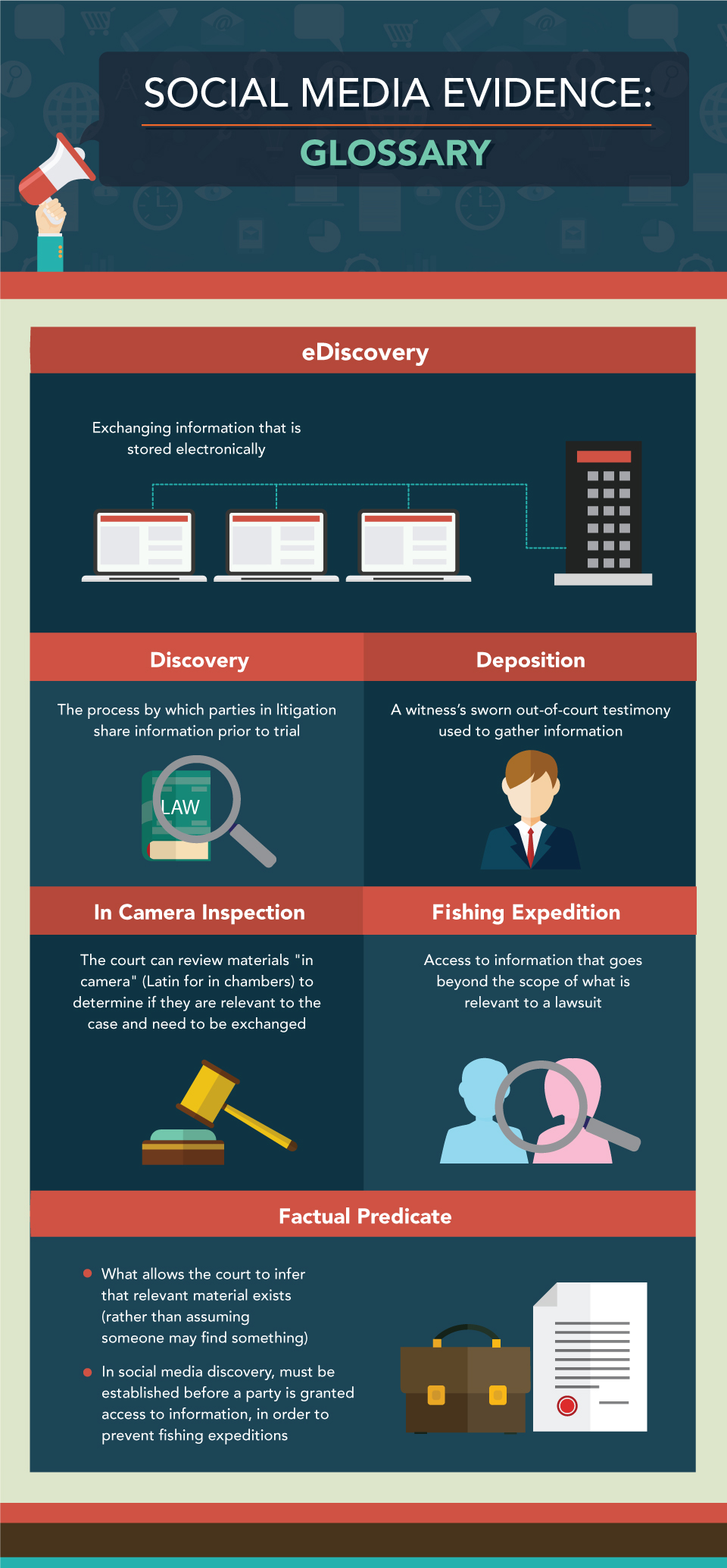

Before we break down social media discovery issues, let's discuss discovery in general. Discovery is the process by which parties in litigation share information prior to trial. Parties are entitled to whatever "information is material and necessary in defending or prosecuting an action." This does not however, give a party the right to uncontrolled and unfettered disclosure. That means they are not permitted to go on a fishing expedition (a term of art used to describe sifting through a person's information in search of anything usable). The courts are given broad discretion in regulating discovery. The interpretation of what is relevant and what is "material and necessary" as well as whether disclosure would be "uncontrolled and unfettered" is a source of contention amongst litigators.

Discovery requests often include medical records and photographs. Taking depositions is another element. This affords each side the opportunity to ask questions that relate to the issues. Often times the depositions uncover more issues relevant to the action and result in further discovery requests.

Private information can be discoverable if material and necessary relevance is established. The Court can compel an individual to provide their adversaries with access to that information. For example, medical records are private, but if you receive treatment for an injury that is part of a lawsuit, those treatment records are relevant, material, and necessary to the litigation. You would be compelled to provide copies of the records or an authorization for the other party to access the records. There is no longer an expectation of privacy when it comes to records relating to that injury.

Further, assume someone testifies that they made a certain number of phone calls, sent a letter, or even wrote in their diary. The relevant portions of those seemingly private communications are discoverable if they are material and necessary. However, if material is discoverable that does not necessarily mean it will be discovered. In order to compel an adversary to exchange something, a party would need to show that they are relevant. In the context of social media, a party needs to establish a "factual predicate" to show that discovery of the materials would likely lead to the exchange of material and necessary information.

The rules governing discovery are well established; how these rules are applied is where things get interesting. The rise of social media has presented a new set of issues. Surely everything an individual posts on Facebook or Instagram isn't relevant to a lawsuit. But what if something is? Because there has been no ruling from the New York Court of Appeals specific to social media discovery, the trial courts and their respective Appellate Divisions have come up with their own interpretations to address these issues. They seek to strike a balance between allowing parties the access to relevant information while also preventing uncontrolled fishing expeditions. In the case summaries below, you'll see how some of the courts in New York State have attempted to strike this balance.

Social Media Discovery Issues

Most social media users have privacy settings activated, which prevents prying eyes from seeing everything they post. Anyone (including attorneys) can typically see if someone maintains an account, even if the contents are limited. If you are a party to a lawsuit, what kind of information would you be compelled to exchange? The answer to this question depends on whether or not the information sought from your social media is relevant to the litigation. Remember, anything that is material and necessary is considered relevant. For social media content otherwise inaccessible, a party needs to demonstrate relevancy through establishing a factual predicate. The factual predicate is what allows the inference to be drawn that relevant material exists, as opposed to the assumption that a person may find something (think: fishing expedition).

Keeping in mind that courts are given broad discretion when ruling on discovery issues, here are some examples of how courts in New York have handled social media discovery requests:

-

A 2010 ruling

in Suffolk County granted full access to a plaintiff's Myspace and Facebook accounts.

The plaintiff maintained throughout the litigation that her serious physical injuries kept her confined to her house and bed. Public portions of her Facebook showed her smiling in locations outside of her home. The court held that this contradiction warranted further inquiry into her social media accounts. The relevancy was established and it was determined that her accounts would likely contain necessary evidence regarding her activities and abilities. The photos were the factual predicate; the relevancy was that it contradicted her testimony so access was granted. This court also noted that the plaintiff was unable to rely on an expectation of privacy, as the purpose of social media is to share information with the understanding that it could become public. -

A 2010 ruling

in the Appellate Division 4th Department (Buffalo & Rochester area) said the defendant's request was too broad.

In this case the defendant requested authorization of the plaintiff's account information. The defendant argued the information was relevant to whether or not the plaintiff had sustained a serious injury in a car accident. The Appellate Division ruled in favor of the plaintiff, because the defendant's request was overly broad and failed to show a factual predicate that would establish relevancy. In this case, the defendant attempted to conduct a fishing expedition. Unlike the Suffolk County case above, there was no contradiction between information previously provided and publicly viewable content. There was nothing to suggest that the social media materials would contain relevant information. -

The 4th Department did the same thing in 2011.

In this case a plaintiff was injured in a motorcycle accident and the defendant sought access to the plaintiff's Facebook and Myspace accounts. The lower court ruled the defendant was entitled to that access. The 4th Department overturned the ruling and said the request for that information was too broad. -

In 2011 the Appellate Division 1st Department (New York City area) also

overturned a lower

court.

The lower court performed an in camera inspection of the plaintiff's Facebook records. An in camera inspection means the court reviews requested records to determine relevancy. In this case, the lower court granted the defendant's request to compel authorization for all Facebook records from the date of the accident onward, including anything deleted or archived. The 1st Department reversed the lower court's ruling because while the in camera review established relevancy of some content a more specific ruling on what pieces of information were relevant was required. They also noted that if content is relevant, privacy settings do not shield it from discovery. -

A 2012 ruling from

the Appellate Division 2nd Department (Long Island & Lower Hudson Valley area) also involved in camera review.

The plaintiff had been injured in a car accident and testified that her injuries impaired her ability to play sports and caused pain worsened by cold weather. Publicly viewable portions of her Facebook page showed the plaintiff on skis in the snow. The lower court ruled the defendant was not entitled to full access of the plaintiff's Facebook, but directed the plaintiff to provide copies of every photo on Facebook depicting the plaintiff participating in sports. The Appellate Division said the photos showed the extent of the plaintiff's abilities. (This was the factual predicate). They stated other Facebook material might contain further relevant evidence. Instead of granting full access, however, they directed the lower court to conduct an in camera inspection of the plaintiff's Facebook to determine which statuses, emails, photographs, and videos were relevant.

Facebook's Role: The Stored Communications Act

In 1986 Congress enacted the Stored Communications Act, which states that a third party providing communication services to the public (i.e. Facebook) is not permitted to divulge the contents of an electronic communication to any person except as provided by the act. When Facebook has been confronted with discovery demands, they have cited this regulation, noting the only exception is if the user consents. This same principle applies to requests for medical records. In accordance with HIPPA regulations, a hospital or doctor must receive authorization before they can release medical records.

In New York State, if a party seeks discovery from a non-party they must show that the information cannot be obtained through other sources. The parties to the litigation are considered the most appropriate source for information. Facebook users are the most probable to access their own information since they possess the username and password to their account. Facebook even gives the option to download all the contents from your profile, including deleted information. While Facebook can release your information if authorized, the ability for a user to get a .zip file of all your contents will likely relieve them of this duty.

What to Expect Going Forward

Moral of the story: Parties are entitled to relevant information and courts have a lot of discretion in determining relevancy. While some lower courts have ruled that all social media content is discoverable if relevancy is established through a factual predicate, the Appellate Divisions primarily hold that this only allows for the discovery of relevant information. While they won't permit a fishing expedition for whatever can be caught, they may allow people to catch relevant fish known to exist. Some jurists are speaking out against the court's performing of in camera reviews, while others argue it's within the court's discretion.

A detail that has been made abundantly clear: Regardless of your privacy settings, if something is determined to be relevant it can be used in court. More time and additional rulings from the higher courts are necessary to determine a universal method to address social media discovery requests.

About the author

Christopher Paddock, Esq. is a plaintiff's personal injury lawyer in New York City. He is a graduate of the City University of New York School of Law.